FLUXING ALUMINUM

Casting of Aluminum 101:

Types of Melting Furnaces

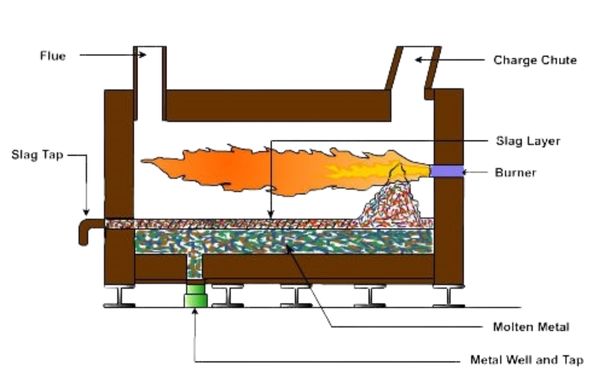

There are several types of furnaces that are used to melt aluminum. The most popular are:

1) Gas fired crucible furnaces

2) Reverberatory furnaces

3) Electric resistance furnaces.

Schematic diagrams of these furnaces are shown below.

There are a multitude of electric furnaces used to melt aluminum. The most popular type is a resistance furnace. An example is shown on the right. Electric induction furnaces can also be used to melt aluminum, but care must be taken in furnace selection as it is preferable to flat melt aluminum as the stirring action of induction melting can lead to more oxide problems.

Regardless of casting method or melting, controls must be employed in the melting process to control the quality of the molten aluminum. Molten aluminum, prior to casting, contains many impurities which, if not removed, cause high scrap loss in casting, or otherwise cause poor metal quality in products fabricated there from. In molten aluminum alloys, the principal objectionable impurities are dissolved hydrogen and suspended non-metallic particles such as the oxides of aluminum and magnesium, refractory particles, etc.

Melting in air, high temperatures, fossil fuel decomposition, humidity, oxide-covered charge materials, returns, trim scrap, gates and runners, and sand system debris all contribute to the presence of melt impurities. Melt treatments such as degassing, adding fluxes by manual addition methods, or by flux injection and/or rotary degassing & fluxing, and filtration are typically the in-process steps employed to control and remove these impurities.

Solid, non-metallic particles suspended in molten aluminum can cause serious difficulties during casting and fabrication of cast parts. These particles consist of oxides that are introduced into the melt with the scrap during the melting, or are produced by direct oxidation with air, water vapor, carbon dioxide and other oxidizing gases while the metal is processed in the molten state. Fine, broken-up oxide films stirred into the molten metal are particularly harmful, since in contrast to more macroscopic oxides and other solid particles, they cannot be skimmed off as dross and instead, remain suspended in the molten aluminum as an emulsion. Solid particles dispersed in the metal can also act as nuclei for the formation of hydrogen bubbles during solidification of the metal. Furthermore, these non-metallic impurities may seriously impair the mechanical properties of the cast part. They can also lead to excessive tool wear during machining operations.

Fluxes should and must be used to control these harmful impurities. The use of flux is not well understood by the average foundryman and many consider fluxes as a black art. Many foundries either

don’t use fluxes, or do not use them regularly. Fluxes need to be used with each heat that is melted.

The main reason that fluxes need to be used when melting aluminum alloys (the melting temperature

range of most industrial aluminum alloys is 1350oF to 1400oF) is because aluminum rapidly forms a

layer or film of aluminum oxide (alumina or Al2O3) on all surfaces when exposed to the atmosphere.

Description of Oxide Formation

Aluminum is an extremely reactive metal. Molten aluminum oxidizes rapidly in air, even in the presence of relatively pure inert gasses if some oxygen is present. Al2O3 and MgO-Al2O3 oxides formed in the bath have nearly the same density (only 5% less) with liquid aluminum; so flotation of oxide inclusions is slow. In the absence of surface tension and trapped gasses, this layer of aluminum oxide would remain on the surface of the furnace and continue until all of the metal was oxidized. Fortunately, the oxide layer is stable due to surface tension factors and remains on the surface protecting the metal from further oxidation. In time, some oxygen will diffuse through the oxide thickening the oxide layer.

However, each time the surface is disturbed, fresh metal is exposed and more oxides are formed. The

oxide films are folded up and broken by furnace convection currents, by mechanical stirring, and by

ladling in typical foundry applications. Some of the disturbed oxides will become emulsified in the liquid aluminum while most of the oxides will remain floating on the surface (called dross).

A layer of dross, when folded back on itself, is porous and will therefore accumulate aluminum beads

in the interstices between dross layers, the trapped aluminum may be several times the weight of the

dross. These aluminum droplets can be released from the oxide by use of fluxes.

Fine oxide particles in molten aluminum tend to remain suspended because their density is close to that

of aluminum and their high specific surface area slows flotation or settling. Moreover, oxides that do

separate from the melt tend to envelop substantial amounts of usable metallic aluminum. In summary,

the propensity for aluminum to oxidize is the main reason fluxes are used.

Fluxes can:

1) Retard oxidation

2) Accelerate inclusion removal

3) Allow for recovering metallic aluminum from dross

4) Clean oxide buildup from furnace side walls.

Ingredients of Fluxes

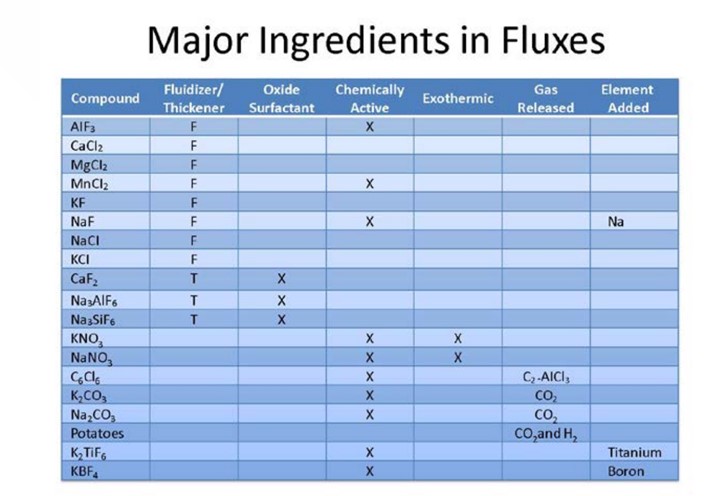

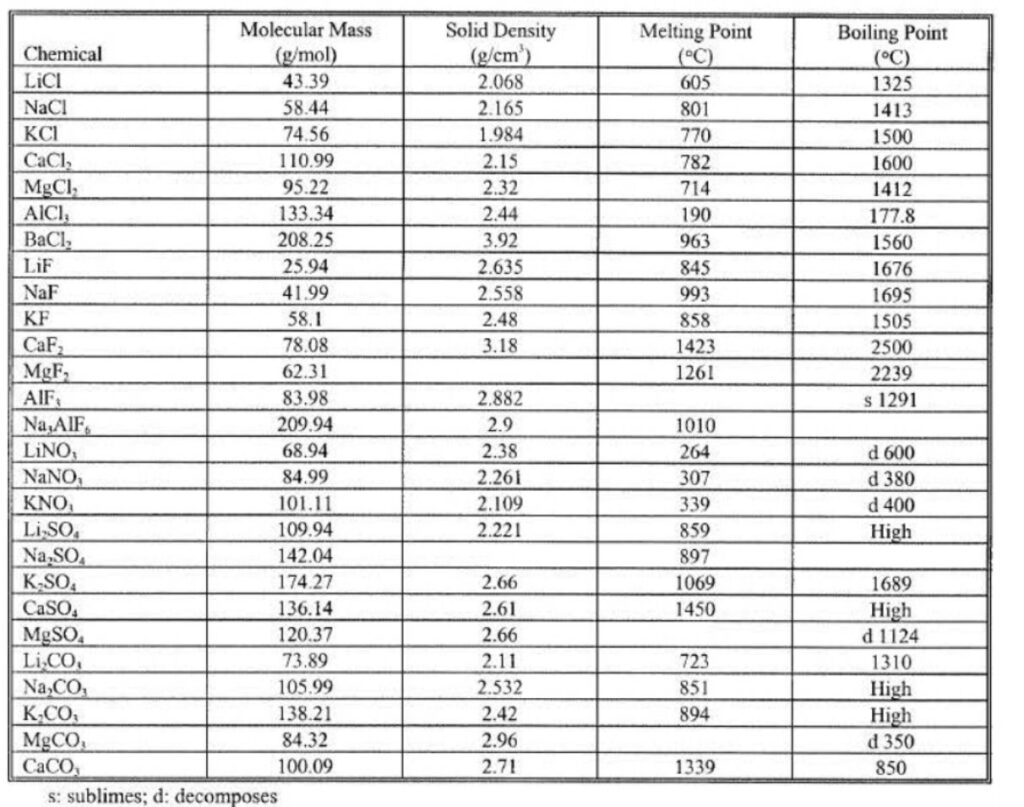

Fluxes are generally based on a mixtures of halide salts (chlorides and fluoride containing compounds). Fluoride salts (such as Cryolite or Sodium Fluoro Aluminate Na3AlF6) are generally blended with Sodium Chloride (NaCl) to increase activity and to improve fluxing action, however, fluoride concentrations are usually be kept low for environmental reasons. Some salts are fluidizers which improve fluidity while others are thickeners which tend to make the salt less fluid and stick together better for skimming. The density of the molten salt is also important so that it will float free and dross easily without producing salt inclusions in the parts.

Major ingredients commonly used in aluminum fluxes and their physical properties is shown in the

tables below:

Physical Properties of Flux Ingredients

Aluminum Fluxes are composed of compounds that impart – Fluidity, Wet ability, Chemically Active,

Exothermic, Gas Released Ability. Just some of the compounds that are used in fluxes are shown in

the above tables and include:

AIF3, CaCI2, MgCI2, MnCI2, KF, NaF, NaCI, KCI, CaF2, Na3AlF6, Na3SiF6, KNO3, NaN03,

C6Cl6, K2CO3, Na2CO3, Potatoes, K2TiF6, KBF4

These compounds or mixtures of provide the following benefits:

- Form low-melting, high-fluidity compounds as is the case with NaCl – KCl or MgCl2 -KCl mixtures.

- Decompose to generate anions, such as fluorides, chlorides, nitrates, carbonates and sulphates, capable of reacting with impurities in the aluminum.

- Act as fillers to lower the cost per kg or to provide a matrix or carrier for active ingredients or adequately cover the melt.

- Absorb or agglomerate reaction products from the fluxing action.

Inexpensive fluxes will only use the bare minimum percentage of the above compounds and thereby

provide minimum benefits. Basically, you get what you pay for.

Classification of Fluxes by Use

There are basically four functions which fluxes provide:

1) Cover Fluxes provide a liquid cover to prevent further oxidation of the melt.

2) Drossing Fluxes assist in the separation of metal from the dross

3) Cleaning and Refining Fluxes that assist in the separation of oxides dispersed in the melt

4) Wall Cleaning, which is removal of the oxides attached to furnace walls. Appendix 1 briefly

describes each aluminum AlucoFlux product.

Cover Fluxes

Cover fluxes generally form a liquid or semi-liquid layer to minimize oxidation and hydrogen absorption. Frequently the furnace operation requires multiple purpose fluxes so that a small amount of a multiple purpose flux is left on the surface as a cover flux. The requirement is that the flux is relatively fluid so that it covers the furnace surface with a continuous liquid layer. Many fluxes can be used successfully as cover fluxes.

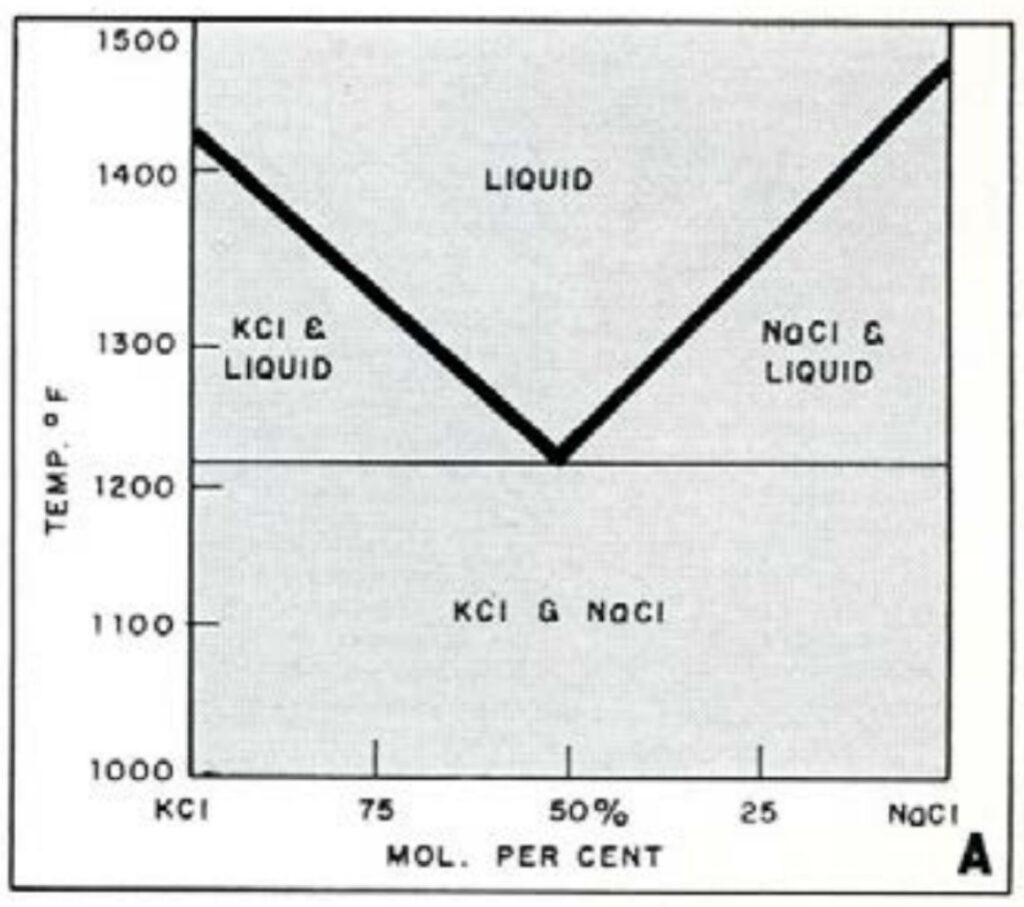

These fluxes are intended to form a protective cover to prevent the formation of oxides during melting or prolonged holding of the melt. This type of flux is particularly useful when finely divided metal charges such as chips, sweepings, and die-casting metal flash are melted. Cover fluxes frequently are added with the solid charge and melt before the metal to form a liquid layer. These fluxes usually are mixtures of chlorides, selected for a suitable density and melting point. Sodium chloride is a major ingredient, but its relatively high melting point requires the addition of one or more salts with lower fusion points to reduce the melting point. A simple example of how the melting point (1428oF) of a sodium chloride (NaCl) salt can be reduced by the addition of potassium chloride (KCl) (1474oF) to 1214oF is shown below with this simple phase diagram. The net effect is that the melting point of both components is reduced. Phase diagrams are the basis for systems which form the basis of commercial cleaning and cover fluxes are formulated. Thus, flux compositions are chosen picked so that the melting points match furnace temperatures.

Drossing Fluxes

Newly formed oxide dross with trapped gasses has a low density and will trap molten aluminum during the metal cleaning and degassing operations. The aluminum droplets appear as fine beads trapped between the oxide layers. It is not unusual for the dross to contain much more than an equal weight of metal since the dross itself is light in weight. Like wet snow the dross, which has a high metal content, will take on a wet appearance and will feel heavy when it is held. Dry dross, like dry snow, is powdery and has a dry appearance. Dry dross is light in weight and falls apart easily. When the furnace is skimmed, any metal remaining in the dross is lost. Drosses thus generated, are often sold to scrap merchants who will at best pay just a partial value for the recovered aluminum at a dross treatment facility. The better option is to treat the dross in the furnace to release the metal directly back into the furnace, saving the metal value and the heat content in the furnace. This operation is termed drossing.

Metal Cleaning Fluxes

The mechanism for cleaning the metal is to wet the oxides with flux so that they will either float or sink but will not stay suspended in the melt. Alternatively, if the flux is rabbled (or stirred) into the melt it is possible to have a cleaning effect several inches below the surface. With enough stirring it is ‘theoretically possible’ to clean a high percentage of the metal. In practice, the rabbling technique is much less effective than the injection technique. Metal cleaning fluxes work best when injected. However, in practice, this is often not accomplished. A combination of gas injection with fluxes has also been shown to be effective for removing hydrogen and oxide films from the melt.

The layer of wet dross on the surface of an un-fluxed bath of molten aluminum consists of a mixture of

oxides and small entrapped globules of molten aluminum. The oxide skin on their surface prevents their agglomeration and collection in the body of the melt. This wet dross can be simply skimmed off, but the metal loss is very high, since the metallic content of such a dross is about 80-90 per cent. There are definite economic advantages to recovering as much as possible of this metal, and this can be done easily with the aid of a cleaning flux.

Straight chloride fluxes are not very effective in this separation, but the addition of fluorides greatly increases their fluxing power. Chemical reactions also occur as cleaning fluxes provide this metal separation. The detached oxides are suspended in the molten flux and produce a gradual thickening.

Cleansing the molten aluminum of emulsified oxides increases the flowability of the molten aluminum

which is important when producing thin casting sections.

Wall Cleaners

Wall cleaners wet the oxides with salts which soften the oxides and allows the operator to easily scrape them from the brick. If scraping after using wall cleaners is done regularly, the furnace walls will stay clean. A solid dense shelf can build on the furnace wall if it is not cleaned. Eventually pieces of this dense shelf break off and sink to the bottom of the furnace. In time the furnace capacity will be reduced to the point where it is necessary to shut down the furnace and mechanically remove the oxides from the bottom and walls. This operation may require a considerable effort if the furnace is not cleaned regularly. Wall cleaners only soften the oxides and do not remove them from the furnace walls. Simply throwing wall cleaner into the furnace without scraping will result in oxide build up and will not clean the furnace. Scraping without wall cleaners generally results in brick damage and dirty furnace operation. Dirty furnaces produce dirty metal and result in more downstream problems in the products.

Furnace Problems without Fluxing

When flux isn’t used, the furnace cleaning operation requires much more force that can result in damaged refractory. If the furnace is not routinely cleaned, oxides and spinels will build-up on the furnace walls, particularly at the metal line. The longer the oxides and spinels stay attached to the refractory, the more tenaciously attached they become, until cleaning becomes very difficult. At this point the furnace must be either hot cleaned or cooled to allow mechanical cleaning with jack hammers. Both of these operations are damaging to the refractory and result in lost production.

Furnace Fluxing

Fluxing may take several forms. Ideally the flux is injected or rabbled under the metal surface where it melts and floats to the surface carrying oxides with it. It then forms a semi-liquid layer on the molten metal which is effective in preventing further oxide contamination and reduces hydrogen pick-up in the melt. At the same time the liquid salts soften the oxides on the walls of the furnace and reduce the bonding of the oxide at the walls. Finally, the liquid flux in contact with the dross layer wets the metal particles so they will coalesce and fall back into the melt.

For melting furnaces, the flux is frequently added with the aluminum charge so that it melts as the metal melts and some salts will wet the surface and reduce oxidation during the melting cycle.

Another application method is to broadcast the flux on the surface of the dross where it melts and works its way down through the dross. This is the most effective method for separating metal from the oxide-dross layer. The flux will chill the dross which is a good insulator so the flux will melt very slowly unless the refractory has been heated with a firing cycle before the addition. If the flux is broadcast during the firing cycle it will vaporize making a heavy smoke. The flux is wasted since it is not retained in the furnace.

Finally, operators can apply the flux to the walls to soften the oxides and spinels so they can be easily

scraped during the cleaning operation. Again, it is best to heat the refractories before the flux operation

since the flux is generally more effective at higher temperatures. Cleaning should be done at the end of

a firing cycle. The same principles apply to crucible fluxing except, that the flux may be added during

the firing cycle as long as there is no direct flame impingement on the flux.

Economics of Fluxing

Fluxing with molten salts is generally a cost saving operation. Ideally, much of the metal is released from the dross by fluxing which saves the cost of transporting and processing excess metal. The cost of the flux is made up easily by the reduction in “melt loss”. An additional bonus is the improved metal cleanliness and the improved furnace cleaning without damaging the refractory as well as saving the cost of re-melting the metal. Removing aluminum oxides, micro-inclusions and hydrogen results in reduced casting scrap, vastly improved mechanical properties of the cast part and improved casting machinability.

Conclusion

Everyone who works with molten aluminum should be concerned with inclusions. Failures in critical parts are expensive. For the manufacture of critical parts, one must start with the cleanest metal possible, maintain a clean furnace, use the best fluxing techniques available, and handle the metal carefully to avoid generating oxides in the pouring operation.